Building material (Susa, 2021), the new novel by the writer Eider Rodriguez (Orereta, 1977), is a work written against silence. This time Rodriguez moves away from stories, the usual format in her work, and addresses a love letter to a recently deceased father after a life marked by alcohol and to herself. In any case, it is a card that, being real, is shown to be honest, passionate, sharp and painful, very far from perfections and idealizations.

Literature serves to unravel and understand, and Building material, written from an unconditional honesty, responds to this objective from the conviction that some things can only be understood if they are written. The narrator of the novel affirms that words have the power to metabolize, and Building material invites us to connect with the reflections and feelings decanted in the memory of Eider Rodriguez, snatched from silence through steely phrases.

We have spoken with Rodriguez about the result of his immersion in so many and so long silences.

why come now Building material? Has the writing process mediated the fact that it is such an intimate story and the consequent implication that this entails?

After I finished writing a story and when I was about to start a new one, I realized that I was going to have a hard time bringing purely fictional characters to life: they seemed like cardboard to me, it was a very strange feeling.

Chatting with the editor, I told her the story that has ended up being Building material. I already had it in my head, although I couldn’t find the courage to write it, among other things because it was based on real people. She was the one who surely gave me the little push I needed. And yes, the process has been different from previous books: once I started writing, the words have come to me like gush.

The book is a sincere exercise in fiction, since, although it has a lot of you, it belongs to fiction. Are you worried about the readings that people can do? What fears did you have before publishing it and what reactions have you received?

The word fiction it makes me uneasy… I find it difficult to name the book using the terms available to us, but I think the one that comes closest to it is that of nonfiction novel. It’s hard for me to call it fiction, even more to talk about autofiction. Instead, the term novel don’t make me worry. So I think the most suitable is nonfiction novel.

About fears, what to say? My greatest fear was how those who appear portrayed and portrayed would look like. In the photos, nobody looks according to the image they have of themselves, right? Furthermore, it would be impossible, because no one is the same seen through other eyes as seen by oneself. The look is subjective, and they were already warned and warned.

So far, I haven’t had any shocks!

‘Building material’

The text exudes pain. In the narration there is no compassion, since, as the narrator says, that would put the writer above the characters and the readers, quite contrary to his aspiration to treat them face to face. What type of reader do you have in mind when you write with the aim of publishing?

Yes, it has been a way of looking at pain face to face. My way of managing fear has been to release it until it has subsided, with its complexity and incoherence. There is also compassion, but the book is not written from that feeling. I would say that there are many feelings; not all beautiful or praiseworthy, but they are all feelings.

I don’t usually have a specific reader in mind. And in this case, even less. It is true that I have written it with the intention of publishing it, but the words come from a deep intimacy. I have moved between two extremes, the public and the private. In the middle, there is the artifice, the novel.

What reward, if any, has the pain that accompanied you during the writing process? The narrator affirms that words have the power to metabolize, but how did you emerge from the writing process?

Writing has helped me, it has been like removing a thorn that is too old. And yes, it has been like that: the very act of writing moves the facts to another place, metabolizes them; It leads you, for example, to review pain, or shame, or dependency, or love, and that review inevitably generates a change.

I think I’ve come out of the process a little freer.

Beyond the duration, what doors has it opened for you and what limits has the change from the story to the novel imposed on you? Have you been forced to sharpen the literary resources more focused on rhythm, such as anaphoras, enumerations, long paragraphs and other shorter ones, dialogues in direct style…?

When writing, I always attach great importance to rhythm. To do this, I have used those resources that you have mentioned and others, such as silences, for example.

There are many ideas, fragments and images, death leaves a little chaos around it, and I didn’t want to give up that feeling of chaos and madness, I wanted it to appear, but to the sound of a dance in which the past, the present, the future, the transcendental and the nonsense, the bills, the orgasms, the broken people, the love and the disgust.

Reading aloud has helped me a lot in that task.

The novel is presented in four chapters. For what is this? What does this sum of points of view contribute to the story and why did you decide to add in the last chapter the letters sent by your father to your mother when he was in the military?

I wanted or needed a lot of layers and textures to reflect the diverse and sometimes conflicting feelings that run through a complex relationship. For this, it was essential for me to use more than one point of view: there is the daughter in the first person; there is the daughter in the third person; there is the father in the first, second and third person; and in all of them is the current and past perspective.

The part about the letters, masterfully translated by Joxe Mari Berasategi, seems fundamental to me, because it is the only moment in which the father speaks with his own voice, without the interference of the daughter.

It is important to listen to the voice of the people, of all the people; Of course, also in literature. They keep unrepeatable and irreplaceable nuances.

Eider Rodriguez

Within the drama, bursts of humor appear from time to time. What place does humor occupy in your conception of literature, even within a history as dark as the one we are dealing with?

Humor is interesting when telling a story because it changes the tone and, therefore, the rhythm, it almost always introduces a small jolt, it forces you to move from where you are…

In a story as sordid as this, he needed humor like plants need the sun; both in life and in literature, for me it is a weapon to advance; Probably the deadliest I have.

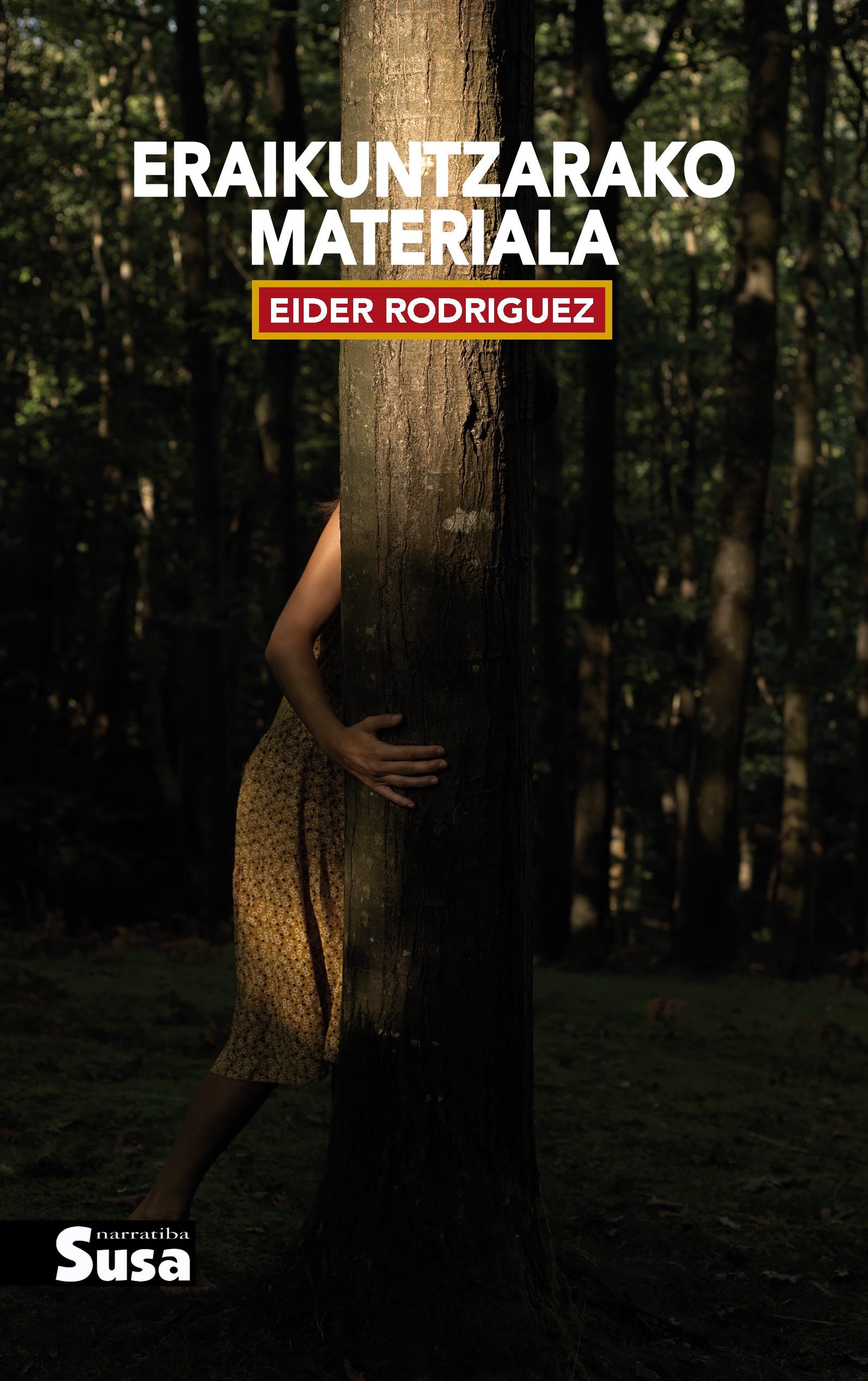

The plants, by the way, have a great presence in the story, starting from the cover itself, and offer a handle amid so much darkness. They are, like humor, rays of light among so much shadow…

Yes, that’s right, but it was after writing the book that I realized the presence of plants… I could give you the same answer as the previous question, but substituting humor for plants.

Plants are insignificant and tiny beings stationed on the margins of the whirlwind in which we live: taking care of them, looking at them… is a gesture of resistance that is as absurd as it is conscious.

The protagonist uses silence against her father, although at the same time she affirms that “the screams that have not been expelled infect my interior”. How does the protagonist experience silence and how have you brought it to the text of Building material?

The book, depending on how you look at it, may be made of fragments. The spaces between these fragments are silences, and for me they are part of the writing, they are very careful elements.

Silence is one more literary resource: there are words about silence, there are silenced passages, but perhaps the most important thing is that in the margins there are blank spaces that are intended to act as cement.

You have explained that while writing the book you have heard The Passion according to Saint Matthew of Bach. How does Eider Rodriguez write? What do you need around or what bothers you?

I wrote about half of the book while listening The Passion according to Saint Matthew, although then I knew nothing about that work (later, Maite Larburu has completed my limited knowledge about the work). Sometimes, I needed a kind of tuning fork to give me the tone, and that’s why I started listening to it.

A large part of the book I have written in bed, and another in coffee shops. To write, I usually need a drink by my side (perhaps not believable, but without alcohol!), and the least number of external stimuli possible. If there is pleasant light, even better.

What three or four books have caught your attention lately?

Two from kilometer zero: “Faith” by Lander Garro and “Flor fané” by Sara Morante; “Karena”, by Alaine Agirre; and “Gu gabe ere”, by Itziar Ugarte.

After a tour de force emotional as the one you have made when writing this book, do you see a great abyss when facing the blank paper again?

I wanted to write fiction, and I’m already satisfying that hunger.

Mario Twitchell is an accomplished author and journalist, known for his insightful and thought-provoking writing on a wide range of topics including general and opinion. He currently works as a writer at 247 news agency, where he has established himself as a respected voice in the industry.