Since 2021, the year in which the Government promised “no more poor people in a rich country”, to date, the living conditions of the population have not only not improved, but have embarked on a divergent path towards worsening, and this in the different dimensions of poverty, whether monetary or non-monetary.

A new dynamic has also been consolidated and a new face of poverty has been drawn. Cities have become impoverished, and most of the population is concentrated in poverty. Worse still, as we will see later, gaps in children’s health persist and worsen, with medium-term consequences for their ability to function in society and to generate future income. In addition to the individual impact of fewer opportunities and freedoms to lead the life they would have wanted and the Constitution promised them, there is also the impact on society as a whole. Untapped productive potential will affect productivity and, therefore, the potential growth of the economy.

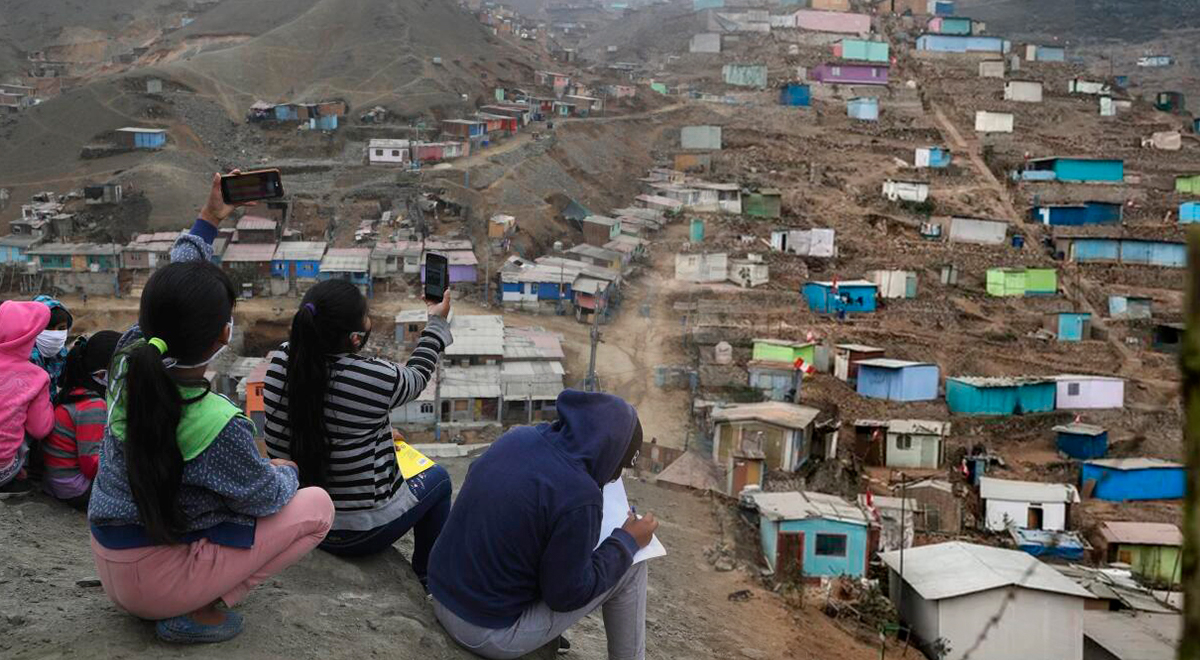

Inflation, weak economic growth in 2022 (+2.6%) and recession in 2023 (-0.6%), as well as the “anti-poor” nature of these developments (for the first time in the last two decades, “redistribution” played against the poor) contributed to poverty increasing for two consecutive years. Compared to pre-pandemic 2019, in 2023 the number of poor people increased by more than 3 million (3,290,000), including 596,000 people in 2023 alone. While the poverty rate in cities almost doubled (from 14.6% to 26.4%), rural poverty continued its slow decline (from 40.8% to 39.8%). The face of poverty has become urban: currently, 73.1% of the poor live in cities (40.5% in the capital). In 2023, almost one in five (18.4%) of the extremely poor will live in the capital.

The incidence of poverty in the capital is already higher than in the departments of Arequipa, Lambayeque, Ica, among others. The capital is no longer the promised land where migrants could realize their aspirations for better living conditions. Lima is an increasingly segregated city: in 2023, poverty in the so-called periphery (where 6 out of 10 Lima residents live or, rather, survive) affects a third (33.8%) of the population, while in the consolidated districts, it affects 20.2%. A more disaggregated look reveals that 60% of poverty is concentrated in the eastern and northern cones. It is also important to note that in the consolidated districts, but of low strata (such as Cercado, Rímac, La Victoria), the incidence of poverty affects one in four people (25.5%). They have been off the radar of social policies. Targeting instruments must be designed that take into account urban heterogeneities.

Poverty has deepened, the poor have become poorer, as revealed by the fact that the poverty gap (the percentage of expenditure they lack to be able to buy the basic consumer basket) has gone, between 2019 and 2023, from 18.3% to 25.3% in the capital, from 20.9% to 23.2% in the rest of the cities and from 26% to 31.9% in rural areas. On the other hand, the financial stress of households is high even in the vulnerable non-poor population. In the capital, 65.9% of the non-poor population, but vulnerable to poverty, barely manages to balance their income and expenses, 15.7% is forced to go into debt and 9.4% to use their savings. This same precariousness is also observed in the rest of the cities and in the countryside.

It is worrying that extreme rural poverty increased in 2023 at the same time as non-extreme poverty decreased. This says a lot about the effectiveness of social programs, particularly food aid and conditional transfers, in offering a minimum survival level to these households. There is an urgent need to re-evaluate the impact of social programs and design new strategies for emergency assistance and development of productive forces that guarantee a lasting way out of poverty.

The increase in extreme poverty is worrying, as it has exacerbated the nutritional deficiencies of the population. In 2023, anemia in children aged 6 to 35 months increased slightly (+0.7 pts.) and remains at a level higher than before the pandemic (43.1% and 40.1%, respectively). Both children in the city (40.2%) and in the countryside (50.3%) are severely affected, which compromises the development of their cognitive abilities and subsequently their academic performance. The accumulation of nutritional deficiencies results in growth retardation (chronic malnutrition). At the national level, their levels remain without showing any progress, although this is the result of an increase in chronic malnutrition in cities (from 7.1% to 8.1%) and a decrease in rural areas (from 23.9% to 20.3%). Considering the population as a whole: In 2023, more than a third (36.3%) will be hungry. It is striking that this problem is more acute in the capital – one in four (43.5%) people in Lima is hungry – than in the rest of the country. This is not a new phenomenon, as the caloric deficit (households that cannot afford to buy the necessary calories) has been increasing and doubling since 2015, when its level reached 19.7%.

In the labour field, the main challenge remains to generate a greater number of suitable jobs; that is, formal jobs, which at least allow workers to access the basic consumer basket, with social protection and labour rights. Income from work, which accounts for more than 70% of total income, has stagnated and adequate employment has progressed little and too slowly. The percentage of working poor (those whose income is insufficient to buy the basic basket, even considering the contribution of other members), has remained stable since 2022 at around 40%. In this second quarter of 2024, it reaches 39.3%, a slight decrease (-1.6pts) compared to the same quarter in 2023.

Among the expected policies we can mention the readjustment of the minimum wage (which has lost 10% of its purchasing power), temporary employment programs aimed at closing infrastructure gaps, incentives for private investment through the reduction of the cost of credits for investments in labor-intensive activities, the expansion of the coverage of social programs and the revaluation of benefits, the design of a new strategy and instruments to fight urban poverty. In the very short term, it is urgent to strengthen food programs and allocate resources to support existing grassroots organizations linked to food (soup kitchens and soup kitchens, associations of small producers) in order to reduce anemia, chronic malnutrition and reduce nutritional deficiencies.

It is no longer time for new promises, but for concrete action, with a short- and long-term vision, to improve the capacity of public institutions to design and implement policies to close gaps and equalize opportunities, particularly for those populations with deep and diverse deprivations.

Source: Larepublica

Alia is a professional author and journalist, working at 247 news agency. She writes on various topics from economy news to general interest pieces, providing readers with relevant and informative content. With years of experience, she brings a unique perspective and in-depth analysis to her work.