Euskaraz irakurri: Itziar Diez from Ultzurrun: “Itzulpenean, alderdi estetikoa eta edukia uztartzen ahalegindu naiz”

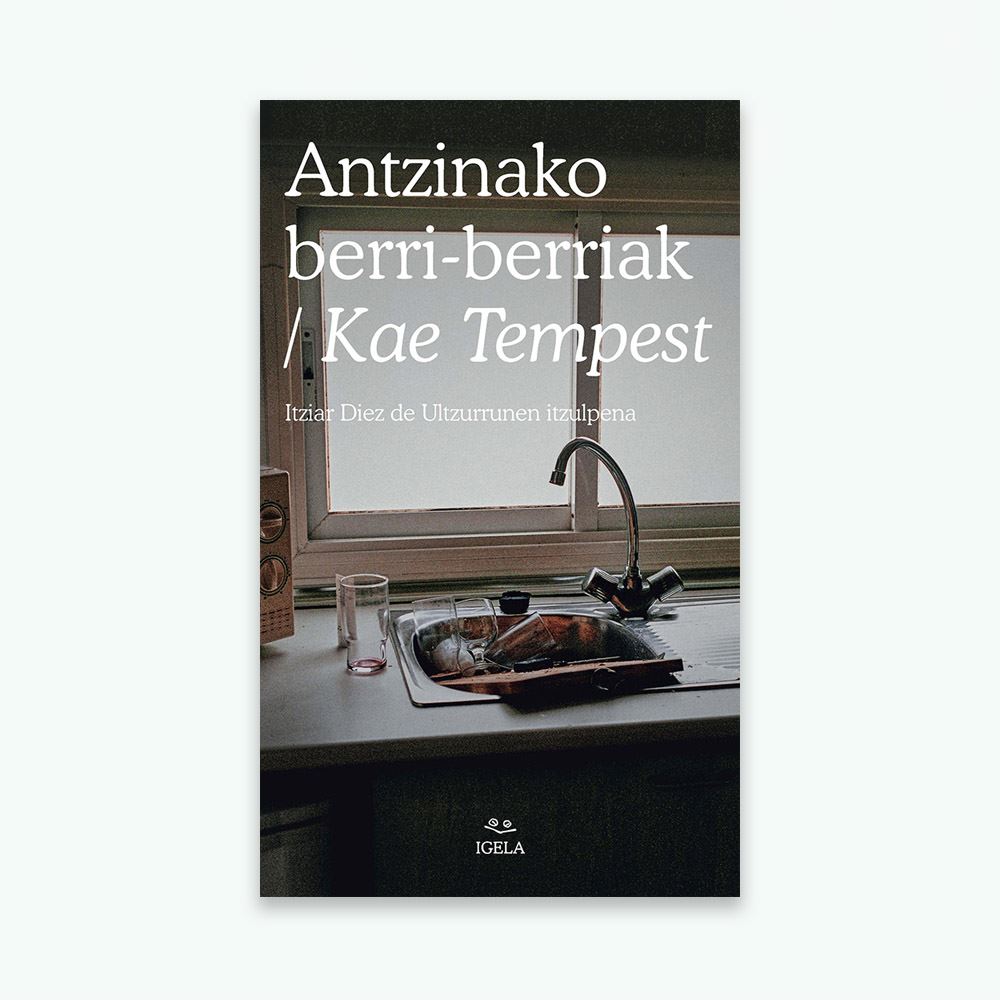

We can already read in Basque a sample of the work Kae Tempest (London, 1985), a non-binary poet and singer: the “poem to read aloud” Antzinako berri-berriak. Thanks to the translation Itziar Diez of Ultzurrunthe Igela publishing house publishes in a bilingual edition in Basque and English the miracles of everyday gods and goddesses (workers, students, fathers and mothers, daughters…) that shine in gray subdued neighborhoods, current and ordinary prodigies that despite everything, or precisely because of all this, they deserve to be counted and sung.

In Antzinako berri-berriak, Tempest captures with sharp vocabulary and lively rhythm the pulse, the beat of the peripheral neighborhoods (serve as an alert on where we place the center, the fact of calling peripherals to our most typical landscapes), and amplifies with the varnish of literature the lights of that collective subject, which are used to being buried by grayness. Sensitively captures, praises and understands the shocking humanity of the dominated people.

We have spoken with the translator Itziar Diez from Ultzurrun.

how did you get Antzinako berri-berriak And what was it that caught your attention about the text?

It came to me through Lander Hawthorn, Igela’s editor. He handed me three works by Kae Tempest, both long poems, and he suggested that I translate one of them. It seemed to Majuelo that Brand New Ancients it was the most appropriate to translate into Basque, and, therefore, it was the first one I read; I did it, moreover, in one go. I loved it, both its form and its content, and I said yes, filled with daring optimism.

Several things caught my attention: the cadence of the poem, the ease with which Tempest links the rhymes, the echoes of ancient epic poems, the rhyme changes in the narrative; the fact that the protagonists are working class people and Tempest sees divinity in them and in their little daily challenges and disputes; the praise of the dignity of the lives of humble people, the sympathetic look of the narrator, the ability to understand pettiness and place it in its context, the denunciation of the false discourse of winners and losers…

Kae Tempest already has quite an abundant body of work. How does the translator immerse herself in the universe of the writer she has to translate?

Yes, it is about someone with an abundant creative work, and who has participated in different artistic disciplines. There was a time when he believed it was necessary to know the author or author very deeply before translating any literary text; In other words, if you wanted to make a translation with a foundation, you had to read the rest of her work, in addition to everything written about him or her and her work.

Now, I have relaxed that opinion. On the one hand, I think we should try to understand the text that we are going to translate in the deepest and most rigorous way possible, and for that it is very useful to immerse ourselves, at least to a certain extent, in the universe of the writer. I say “to a certain extent” because, if the author or the author you are going to translate is very prolific and dozens or hundreds of books have been written about him or her, it is usually impossible to read everything, since we have to take into account that there is a specific deadline to finish the translation and that we have to attend to other daily tasks such as care.

Therefore, this topic does not concern me as much as it did a while ago. I try to get to know the author and her work, but accepting that I will never learn enough to write a thesis about him or her and that, despite this, I will be able to make a correct translation or, at least, I will have that intention.

How has that approach been, in your case?

In this case, I didn’t know Tempest, I hadn’t heard anything about her, and, before starting to translate, I decided to find out more, of course. After that “documentation” work, while I was translating, I have listened to some of his work, to set the scene for the translation a bit, and I think that has helped me.

On the other hand, on the Internet there is a small audio of the show that he created with Bran New Ancientsand I’ve worn it many times: listening to Tempest recite the poem became a bit of an obsession once I finished a first draft and started polishing up the translation, but I don’t think it did me any harm, or at least I hope so.

The job of translating requires by definition a certain flexibility. What margin have you reserved to move away from the original?

I think that I always try to adapt the texts so that they can be read in correct Basque and without obstacles in the way, and I stay as far away as that purpose requires. Before translating Tempest’s poem, I made two decisions: that I was going to present it in a poem style, and that I was not going to twist the text to fit within those formal limits. Therefore, I have tried to translate it within certain formal limits that, precisely, have forced me to move away from the original, although sometimes they have also allowed me a certain freedom because it is impossible to literally translate all the verses.

It seems that, to translate poetry, there would only be two options: literally translate the content of the original poem without adhering to formal limits or prioritizing the aesthetic aspect of poetry and carry out the translation favoring that formal beauty and even making the translation more confusing. I have opted for an intermediate route: trying to merge the aesthetic aspect and the content.

You have searched for the rhyme but, obviously, without sticking inflexibly to the original English. How have you worked on that aspect?

I have tried to use rhymes and respect the cadence of the poem, but without forcing the content, since I have tried at all times to translate the content of the original text in an understandable way, because part of the beauty of this poem resides in that language so Sure.

The truth is that I don’t really know how I have worked on it, I think I have oscillated like a tightrope walker and that reading the translation aloud has helped me a lot, not trying to make impossible rhymes and authorizing myself to use all the linguistic resources at my disposal.

Kae Tempest

Rhythm is one of the most prominent formal elements of the poem. What obstacles have you faced and what resources have you used to bring this growing pace that ends up out of control into Basque?

To maintain the cadence, I have tried to maintain the lightness and speed of the original text, and the main “obstacle” in this task has been the fact that in English the same content can be given with shorter verses. That has been, therefore, one of the difficulties, how to abbreviate verses that are too long so as not to hinder the rhythm but maintaining the meaning, taking care of the comprehensibility and, when it seemed possible, using rhyme.

The poem opens with the notation “This poem was written to be read aloud.” What does this orality contribute to the text? How many times have you read the text aloud?

This orality has led the poem to the line that I was commenting on: a text that could be read quickly had to be created, for which I have used both the syntactic flexibility of Basque and the richness of our vocabulary.

I couldn’t tell you exactly how many times I’ve read the entire text out loud, but I’m sure more than once; and especially some fragments, many times. It has also helped me to listen to the Tempest recital. While she is reciting the poem, she uses the tempos and the strength of her voice to change the rhythms, to amplify the drama of some passages, to highlight some rhymes… She does an incredible job of interpretation.

The translation is bringing us several important jewels in recent times. How do you see the state of health of literary translation in Basque?

Literary translation is in very good health: there are translation professionals who are perfectly prepared, and many of them are willing to work. I would also like to highlight that we have many linguistic resources within our reach, that there is great solidarity among translators and that we are very generous, always willing to help others. I think that shows in the quality of our translations.

On the other hand, there are also publishers interested in translating works of different genres, and some of them are making tremendous efforts in this regard. It should be noted that all the works translated into Basque already form a magnificent heritage. Obviously, that heritage is not as big as we would like, and we have to work to expand it and make it more diverse; In any case, many interesting authors and works of great quality have already been translated into Basque: we have precious books, translated with great foundation and skill. Finally, this good moment also shows that our work is being recognized and that the prejudices that existed some time ago have lost their strength.

Unfortunately, there are still people who do not realize or do not want to realize the contribution that literary translation (and translation in general) makes to the Basque cultural ecosystem. We need stronger policies that favor translation, because our field is key to promoting a taste for reading in Basque. We have to continue working to extend the habit of reading in Basque to the best authors in the world and for that we have to refine different aspects, but, first of all, we have to be able to have these and those authors in Basque.

What translations have caught your attention lately?

In recent times, I have read pushak by Irene Pujadas, a collection of short stories wonderfully translated by Amaia Apalauza, and Waldenby Henry David Thoreau, an essay published by Katakrak and brilliantly translated into Basque by Danele Sarriugarte.

What books are you going to look for in Durango, if you have a choice?

In Durango, I would like to buy, among others, atsoa written by Catarina Albert i Paradís under the pseudonym Victor Catalá, edited by Txalaparta and translated by Sagastibeltza; and the latest from EIZIE’s Unibertsala Literature collection: Winesburg, Ohio, by Sherwood Anderson, translated by Joannes Jauregi.

Source: Eitb

Mario Twitchell is an accomplished author and journalist, known for his insightful and thought-provoking writing on a wide range of topics including general and opinion. He currently works as a writer at 247 news agency, where he has established himself as a respected voice in the industry.